The New York Times, July 24, 2004 pA4

A Chinese Bookworm Raises Her Voice in Cyberspace.

(Foreign Desk)(THE SATURDAY PROFILE) by Jim Yardley.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2004 The New York Times Company

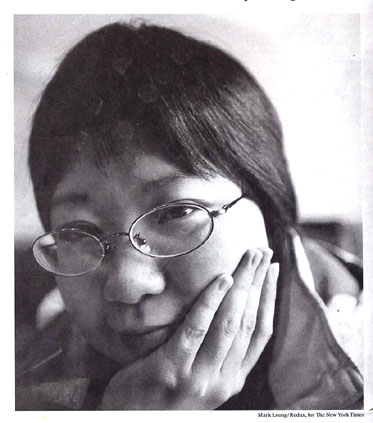

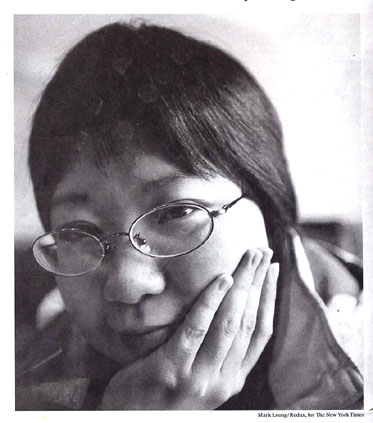

The restaurant in the fashionable Qianhai district is almost empty, courtesy

of the afternoon rains, though a small young woman is sitting on an upstairs

sofa, slightly uncomfortable in her chic surroundings. With her oval glasses,

shy demeanor and slightly hunched posture, the woman, Liu Di, looks like a

bookworm.

What she does not look like is a threat to anything, certainly not China's

government. Yet the government has already imprisoned her for a year. In recent

months, during significant dates on the political calendar, officials have

posted security officers outside the Beijing apartment she shares with her

grandmother. ''They think I'm a dangerous figure,'' said Ms. Liu, 23, giggling

slightly at the thought as she picked at a Thai rice dish.

It is Ms. Liu's other identity that has made her a target of the Communist

Party. Known on the Internet as Stainless Steel Mouse, she is a dissident whose

incarceration over her writings attracted international attention from human

rights groups that demanded, and eventually helped win, her release.

| Even now, roughly eight months after she was freed, Ms. Liu

must live a watchful life. Upon her release, she resumed her studies at

Beijing Normal University, yet for months administrators left it unclear

whether she would be allowed to graduate. She monitored courses until she

was finally awarded her diploma in late June with a degree in psychology.

She did not attend the ceremony.

She still does not have a full-time job, nor is she certain when, if

ever, she will cease to draw the government's attention. It has been a

disorienting, dizzying ride for a quiet woman who rarely grants interviews

and who says she has always felt like something of a misfit. It was, in

fact, in cyberspace where she first felt accepted. ''To me, the Internet is

a huge virtual space,'' she said. ''It is so different from real life. You

can be more free.''

MS. LIU first logged onto that other world when she was in college. She

had grown up in Beijing in a family that revered books. Her father worked in

the library of the China Fine Arts Museum, while her mother was a factory

worker who died when she was 15. Her grandmother was a reporter for the

government's main newspaper, People's Daily. |

|

|

| An awkward and shy child, she retreated into books,

particularly science fiction. She was struck by Orwell's ''1984,'' with its

grim warning against totalitarianism. ''It's very horrific,'' she said. ''I

had never thought about how human nature could be so dark.'' |

|

"To me the internet is a huge virtual space. It is so

different from real life. You can be more free." Liu Di |

By middle school, she had decided to become a writer and chose psychology as

her college major because to write she thought she ''needed to know more about

human beings.''

On campus in 2000, Ms. Liu noticed other students staring into their

computers. ''A lot of other students were logging on, so I started,'' she said.

She combed through online college bulletin boards and personal Web sites before

searching deeper and finding voices of discontent. ''There were a lot of

opinions and stories that couldn't be seen in newspapers,'' she recalled. ''I

liked it.''

In cyberspace, Ms. Liu found her community. She plumbed literature for a nom

de plume, trying Clockwork Orange and Banana Fish (a J.D. Salinger reference)

before settling on Stainless Steel Mouse, from the science fiction of Harry

Harrison.

She began participating in discussions on a Web site called ''Democracy and

Freedom,'' which is often at odds with the government. By 2001, she opened her

own site, much of it dedicated to literature, but she also published some

articles calling for more freedom. As cyberspace became her home, she began to

defend what the Chinese call netcitizens.

She wrote an essay defending a man jailed because of political postings on

his Web site. She defended another intellectual singled out by the government

for organizing a reading association and for posting political essays online.

She wrote a critical attack on an advocate of nationalism and began dabbling in

satire and parody at the government's expense.

In one posting, she called for the organization of a new political party in

which anyone could join and everyone could be chairman. She said it was a spoof.

But by September 2002, college administrators issued a warning. ''They said the

postings I published on the Web went too far,'' she said. ''Some of the stuff I

thought was written in a joking manner. But they thought it was too far.''

Terrified, she said, she scaled back on her online writing. But two months

later, administrators ordered her to the campus police station, where officers

took her to a Beijing prison. She was put in a cell with three other women,

including a convicted murderer. Even today, she says she does not know which of

her essays led to her arrest.

''I think a normal government should not be challenged by these writings,''

she said. ''We are not promoting violence. We're not organizing to challenge the

government.''

In prison, she underwent some interrogation sessions. She said that she was

frightened initially but that she was treated fairly well. She said that she had

two meetings with a lawyer, and that her family was allowed to bring her books,

magazines and university textbooks. She also learned from a guard that she was

becoming famous in the outside world.

Human rights groups were holding up her case to protest the government's

treatment of Internet dissidents. Shortly before Prime Minister Wen Jiabao was

scheduled to visit the United States last November, the government suddenly

released Ms. Liu and two other Internet dissidents. Her father escorted her from

the prison, and she cried when she got home.

Of the international outcry over her arrest, Ms. Liu said she was stunned.

''I'm delighted that people care about me,'' she said.

SHE spent her first month out of prison under house arrest at her father's

apartment. Then, on Christmas Day, she was told house arrest had ended. In the

end, she said she was never formally charged with a crime. But since her

release, security officers have twice been posted outside her apartment -- in

March, during the annual meeting of the National People's Congress, China's

legislature and on June 4, the 15th anniversary of the government crackdown

against pro-democracy protesters at Tiananmen Square.

Even so, Ms. Liu has resumed writing. Several months ago, she signed an

online petition calling for the release of Du Daobin, another online Internet

essayist. (Mr. Du had been jailed after calling for her release from prison. He

was recently convicted of subversion but was given a suspended sentence.) She

recently wrote an article in a Hong Kong magazine criticizing the arrest of two

crusading newspaper editors in southern China.

Asked why she takes such risks given her history, she said, ''It's the right

thing for me to do, so I'm going to keep doing it.''

She still surfs the Internet late into the night. Government monitors have

managed to block her name Stainless Steel Mouse from some Web sites. But she

said she sometimes uses another moniker: Titanium Alloy Mouse.

''Stainless

steel is low end,'' she said, smiling. ''Titanium steel is much higher end.''